Online patient groups and communities can be a really great thing. They provide a source of support and camaraderie to many people, and the benefit of that can’t be overstated. They can also be a major source of information for a lot of people. However, while good information can be found, online patient groups are best characterized as unreliable sources of information. For instance, there are many well-meaning people sharing questionable or downright incorrect information in patient groups. While people can become an expert on their own personal experiences and condition, this does not in any way guarantee that the information they share is accurate or well-researched. At times, there are even less-than-well-meaning individuals who use fantastic claims to market their products and services to vulnerable individuals. In other cases, people and companies do little more than promote their website’s content to increase ad revenue through clicks.

It can be difficult at times to realize the limitations of one’s own knowledge. That problem is only compounded by the struggle of knowing when someone else is speaking on something outside the limit of their knowledge. This can make it tough to quickly discern good information from bad. While perusing different patient forums and pages, one is bound to see some very confidently and matter-of-factly stated beliefs or claims. The way that something is stated can have a big effect on how others perceive it; so, when someone seems very confident about what he’s saying, it may influence others to assume that he’s confident because he’s right. That can be a dangerous assumption to make, particulary when the topic is related to one’s health. Bad information and poor health literacy are associated with worse health outcomes for patients. 1https://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsliteracy.htm 2https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2966655/

Facebook happens to be where a large percentage of patient support groups exist, and this presents an additional problem. Facebook groups and pages are not particularly easy to moderate, even in rare cases where the moderators have specific guidelines and are active 24 hours/day. If a question is posted in a group or on a page, many people who choose to respond will do so before reading any previous responses. This means there is a lot of noise and repetition and often a lack of real conversation; it becomes far too easy for well-informed responses to be buried among all of the others. Ultimately, this problem exists in most, if not all, social media-based communities to some degree.

With all of the noise and misinformation out there, it’s necessary for people to develop ways to help evaluate claims and filter information shared in patient groups. One such approach is the ability to recognize logical fallacies.

What is a logical fallacy?

According to logician Dr. Gary Curtis of the Fallacy Files, “‘a fallacy’ is a mistake, and a ‘logical’ fallacy is a mistake in reasoning”. 3http://www.fallacyfiles.org/introtof.html What this typically means is that a conclusion is made based on premisses that do not logically support it. When someone makes a claim using an illogical argument, they are committing a logical fallacy. There are many types of specific fallacies that a person could make. In this article, I will cover a handful that I think are relevant to the online patient experience.

Pay attention to the claims people make, and what sort of rationale they use to support the claims. It’s also helpful to pay attention to whether or not you are committing logical fallacies when evaluating new information. Everyone does it; we all have various biases and preconceived ideas that can shape the way we approach new ideas. However, by learning about some common errors in reasoning, we can improve our ability to think critically.

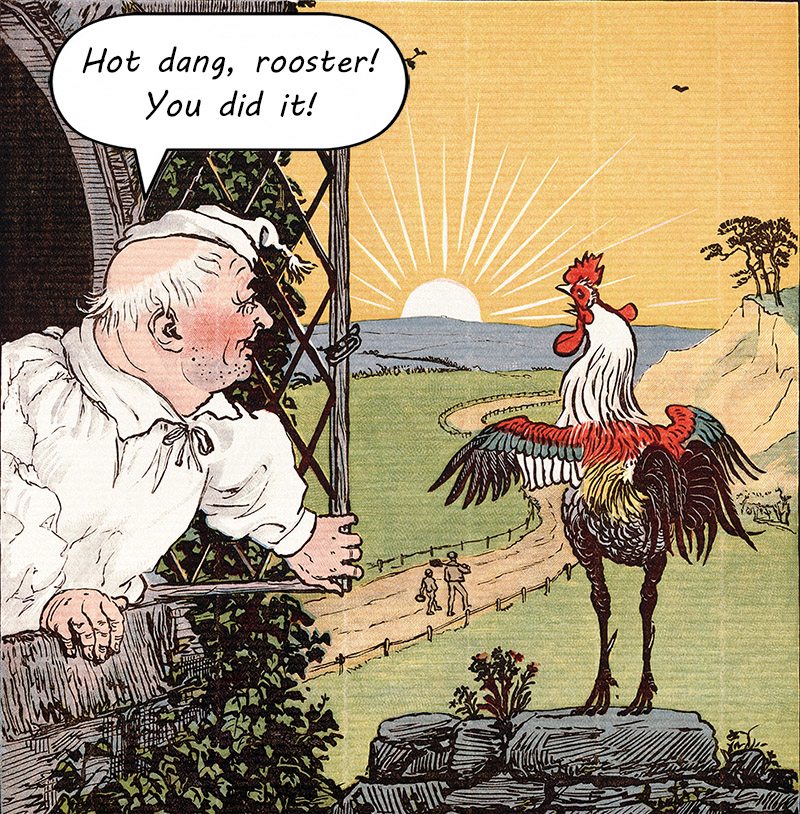

Fallacy #1: Rooster Syndrome

(aka After This, Therefore Because This)

(aka After This, Therefore Because This)

Rooster Syndrome is my favorite name for what’s more properly referred to in Latin as Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc, which translates to “after this, therefore because this”. This fallacy occurs when an assumption is made that because one event precedes another, the first event must have caused the second. It’s also referred to as Correlation vs. Causation, since the fallacy is a matter of mistaking a relationship or correlation between things for one of those things causing the other. 4http://www.fallacyfiles.org/posthocf.html

Rooster Syndrome is my favorite name for what’s more properly referred to in Latin as Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc, which translates to “after this, therefore because this”. This fallacy occurs when an assumption is made that because one event precedes another, the first event must have caused the second. It’s also referred to as Correlation vs. Causation, since the fallacy is a matter of mistaking a relationship or correlation between things for one of those things causing the other. 4http://www.fallacyfiles.org/posthocf.html

Imagine a farmer in the distant past waking up each morning to the sound of a rooster crowing. He gets up and looks outside to see light from the sun just beginning to appear over the horizon. Every day this happens. The rooster crows and the man wakes up to see the sun rising. The farmer thinks this:

The rooster crows

Shortly after, the sun appears over the horizon

Therefore, the rooster causes the sun to appear

Is the rooster causing the sun to rise? To this man from bygone times, it sure seems so! Of course, we know that’s not really the case. The rooster is crowing because it has a biological impetus to crow in anticipation of dawn, based on its circadian rhythm. 5https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982213001863 6https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/asj.12677 But, it’s not hard to see how someone could mistake the crow for being the cause of the sunrise if they didn’t have more information about the world (and the solar system) to work with.

This is an issue that people can be particularly susceptible to – jumping to conclusions about the cause of an event due to incomplete information or lack of context. It can be very easy and intuitive to notice patterns; but actually knowing what, if anything, a pattern means is completely different.

The topic of hair loss is quite common in IBD patient groups. When the topic comes up, it’s almost always in relation to some medication(s) used to treat IBD. There are often a lot of comments saying things like: “I lost hair after starting medication X” and “I started this new medication a couple months ago, and it’s causing my hair to fall out! When will it stop?”.

There are a lot of assumptions being made about the cause of hair loss. Here is how a common reasoning might look:

I started a new medication

Shortly after, some of my hair fell out

Therefore, the medication caused my hair to fall out

It’s completely understandable why someone would assume the medication is causing the hair loss. It seems intuitively obvious that if the hair loss begins not long after starting a new medication, that the medication must be the cause of the hair loss. However, it is far more likely that the person is experiencing telogen effluvium hair loss caused by the IBD itself. This is not a commonly known condition, so most people are not going to see the connection between the symptom (hair loss) and the condition (telogen effluvium caused by IBD). In other words, our intuition may not be working with the best information.

Once one understands the process behind telogen effluvium, including the growth phases of hair and the way a disease like IBD can interfere with them, it’s much easier to look beyond what initially seems like the obvious cause (i.e. medication). In fact, hair loss from telogen effluvium can even be a sign that a person’s IBD is improving (i.e. the inflammation is subsiding). I go into more detail about how telogen effluvium works, and why it is the most common cause of hair loss associated with IBD here: Telogen Effluvium Hair Loss in IBD. A major concern that I point out in the hair loss article is that many people have discontinued a medication because they are convinced it’s the cause of their hair loss – in reality, the medication may have been the one thing treating the IBD, which would ultimately lead to new and healthier hair growth.

Fallacy #2: Unrepresentative Sample Fallacy

(aka Biased Sample)

(aka Biased Sample)

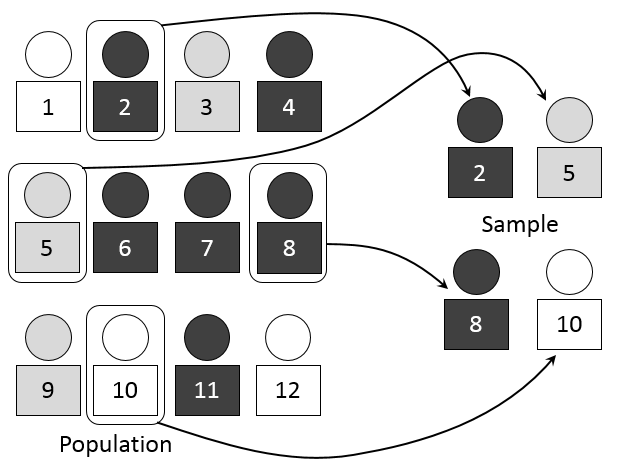

The ‘Unrepresentative Sample’ Fallacy occurs when a conclusion is made about a group of people (or some other thing) based on a selection of the group that doesn’t accurately reflect the true characteristics of the overall group. 7http://www.fallacyfiles.org/biassamp.html Whenever someone asks a question in a patient forum with the goal of getting some kind of consensus among patients, this sort of fallacy comes into play.

Imagine that a person made a post in a patient forum asking, “Has anyone had a bad experience with medication X?”. 75% of the people who responded to the post wrote that yes, they did have a bad experience with medication X. But, this does not mean that 75% of people who have taken this medication had a bad experience with it, and to come to that sort of conclusion based on the responses is to commit an unrepresentative sample fallacy.

In this example, the fallacious reasoning looks a bit like this:

75% of the people who responded to my question have had a bad experience with medication X

Therefore, 75% of people who have used medication X have had a bad experience with it.

More generally, it can be represented like this:

75% of sample S has characteristic C.

Therefore, 75% of population P has characteristic C.

Warning: Simplified primer on statistics incoming…

In statistics, the population is the entire group of people (or things, creatures, cases, etc) that you’re trying to describe or learn something about. In our example above, the population is ‘all people with IBD who have taken medication X’. It’s usually impractical or impossible to collect data on each and every person in the population, so a portion of the population is carefully selected for study – this is the sample. In properly conducted research, there are very deliberate steps taken to ensure that the sample represents the overall population accurately; when it doesn’t, this means the sample is unrepresentative of the population, and any conclusions made about the sample cannot be applied to the population. 8https://www.openintro.org/stat/textbook.php?stat_book=os

Simple Random Sampling: a method for selecting individuals from a population so that each member has an equal chance of being selected.

Generally speaking, for the sample to be an accurate representation of the population, each person must have an equal chance of being selected – this is done through randomization. The illustration above shows simple random sampling. This method is like giving each person a single raffle ticket, and then randomly selecting a set number of tickets.

Another name for Unrepresentative Sample Fallacy is Biased Sample Fallacy. Bias essentially refers to the way a study’s methodology can over- or underemphasize certain features or outcomes over others, ultimately creating a discrepancy between the characteristics of a sample and the characteristics of the population the sample came from. 9https://web.ma.utexas.edu/users/mks/statmistakes/biasedsampling.html When a sample is biased, any conclusions drawn from it will be inherently flawed. When people in a patient forum respond to a question like “Has anyone had a bad experience with medication X?”, there are multiple types of biases that can come into play. In other words, there is no reason to think that the sample (the people who are responding to the post) can accurately and reliably represent the population (all people with IBD who have taken medication X). These are a few of the key reasons why this is:

- The people who are active members of online patient forums may be more likely than the average patient to have ongoing struggles and more complicated health issues. In other words, we can’t assume that the members of an online patient forum accurately reflect the overall patient population. This introduces self-selection bias, as the members of the online community are all there because they chose to join, and not because they collectively represent the patient population. 10http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n526.xml

- Every member of an online patient forum does not respond to every question or post. The type of question, for instance, can really determine a lot about the people who are going to respond. In our example where someone asks “has anyone had a bad experience with medication X?”, the people who have had a bad experience are more likely to respond compared to those who have had a good or neutral experience. A leading question like this introduces a response bias, as people with negative experiences are more likely to respond. It also introduces non-response bias, as there is no way to take into account what sort of answer would be given by all of the people who didn’t respond. 11https://stattrek.com/statistics/dictionary.aspx?definition=response%20bias 12http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n486.xml

- Since the person asking the question is directing it at people who are conveniently accessible (i.e. members of an online patient forum) rather than a selection of people who are likely to represent the overall population, it can be characterized as convenience sampling. This type of sampling is very prone to bias; in part because randomization is not an inherent feature of it. 13http://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods/n105.xml

It can be immensely helpful to share experiences with other people who have been through similar. 14https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18778909 However, it’s important not to mistake the answers given in online patient communities for accurate representations of the overall patient experience.

Fallacy #3: Appeal to Nature

‘Appeal to nature’ represents the notion that what is natural is presumed to be “good” and, by extension, what is unnatural is “bad”. 15http://www.fallacyfiles.org/adnature.html If you frequent any patients groups, online or not, you are likely to come across this. Unfortunately, people often do not hold products or purported treatments to reasonable standards when they believe them to be “natural”. 16https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9738094 17https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2000907/ Broken down, an argument that commits this fallacy might look like this:

This supplement is natural

Natural is good

Therefore, this supplement is good

This sort of argument contains two glaring issues. First, there is no clear definition of “natural”; if you poll a group of people to define “natural”, you are bound to get a variety of answers. Second, there is no reason to assume that something deemed “natural” is good, healthy, or safe.

It can be very quickly demonstrated that the idea that “anything natural is good, healthy, or safe” is simply not based in reality. Nature is full of things that can and will kill you given the right opportunity or motivation. Lions, for instance; no “appeal to nature” will change the fact that a grown lion could kill you with one lazy swipe of its paw.

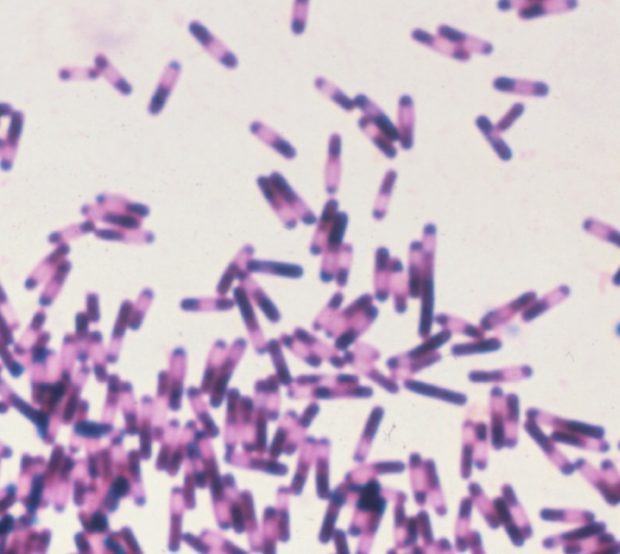

All natural Clostridioides difficile.

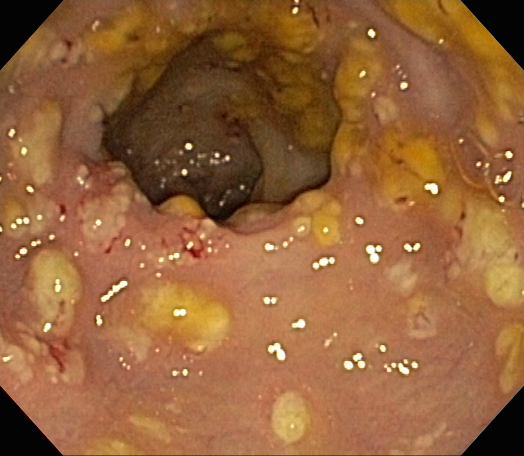

Now, consider Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile), commonly known as “C. diff”. Clostridioides difficile is a bacterium that can cause very serious infections in the human digestive tract. Common symptoms of C. diff infection include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fever. 18https://medlineplus.gov/clostridiumdifficileinfections.html 19https://www.uptodate.com/contents/antibiotic-associated-diarrhea-caused-by-clostridioides-formerly-clostridium-difficile-beyond-the-basics?search=antibiotic-associated-diarrhea-caused-by-clostridium-difficile-beyond-the-basics&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 C. diff infection can also cause pseudomembranous colitis (pictured below), which can lead to toxic megacolon; in which case, a partial or total colectomy may be necessary to avoid a fatal outcome. 20https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000248.htm But, C. diff is at least as natural as the bacteria in probiotic supplements!

This is a normal colon, unravaged by C. diff infection. |

This is a colon with Pseudomembranous colitis caused by C. diff infection. |

When used in an appeal to nature fallacy, “natural” is a loaded term. Rather than describing something, it’s actually placing a positive value judgment on it. Even if everyone could agree what natural means, there would still be a need to explain why it should automatically confer a positive value judgement. Without that, the argument starts looking like this:

This thing is natural good

Good is good

Therefore, this thing is good

And that’s clearly ridiculous!

Look beyond the term “natural” to see what, if any, information is actually being shared.

Fallacy #4: Appeal to Ignorance

Also known as Argument from Ignorance or Argument to Ignorance (Latin: Argumentum ad Ignorantiam); this is the assumption that something is true simply because one is not aware of any evidence against it. 21http://www.fallacyfiles.org/ignorant.html You may have heard the phrase “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, meaning that if one makes a strong claim, one should be able to provide equally strong evidence to back it up. 22https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sagan_standard Without sufficient evidence, it would be reasonable to view the claim as dubious. Note that strong evidence does not mean anecdotes, testimonials, or a book written by someone selling something based on the claim. Strong evidence in the medical world refers to things like Cochrane reviews (and other systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. 23https://www.cebm.net/2009/06/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/

Consider a scenario in a patient community where someone makes a claim that sounds too fantastical, too perfect, to be true. For instance, someone may claim that IBD can be treated by chiropractic manipulation rather than medication. When challenged to back up this claim, the person may attempt to defend their position with an ‘appeal to ignorance’. Here is one example of how that situation might look:

Person A: Chiropractic adjustments can treat or even cure IBD!

Person B: There’s no evidence of that.

Person A: Yeah? Well, show me evidence that it can’t!

Do not settle for this. At times, this is a deliberate tactic used by unethical individuals to promote their brand or services. Often, though, it’s made by people who don’t see the flaw in their own reasoning.

There exists a phenomenon where people hold alternative treatment ideas to a far lower standard of evidence than they would expect from so-called “conventional” treatments. 24https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9738094 25https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2000907/ If people held all supposed treatments to equal standards, there would surely be a remarkable decline in supplement and alternative therapy sales. At the very least, one should never fall for the claim that if there is no evidence against a supposed treatment, that that is as good as evidence in favor of it.

There are a lot of really ridiculous treatment ideas out there that have never been formally studied (meaning well-designed scientific studies with human subjects). Does this mean they are good ideas? Absolutely not. If someone insisted that you should believe that bathing in Styrofoam™️ packing peanuts will treat IBD simply because “there are no studies disproving it”, would you? Some treatment ideas are simply not worth the time and resources that would be needed to scientifically study it, as there’s just no reason to think they might be viable options.

Fallacy #5: Fallacy Fallacy

Knowing that an argument commits a logical fallacy doesn’t actually tell us that the point being argued is false. Assuming that something is incorrect just because the argument for it commits a fallacy is known as the Fallacy Fallacy. 26http://www.fallacyfiles.org/fallfall.html

There are times when someone uses faulty arguments to support a claim that is actually true.

Being critical of claims is advisable. But, just because one argument in favor of a claim is fallacious, that does not necessarily mean that other arguments for it will be as well. Nevertheless, the burden of proof is always on the person making the claim. 27https://www.trans-lex.org/966000/_/distribution-of-burden-of-proof/

Beyond Fallacies

Determining what is true and false goes beyond understanding and detecting logical fallacies. Making medical decisions can be a particularly difficult task, and there often isn’t a clear cut best answer or decision. In the real world of a person with a chronic illness like IBD, the decision-making process is something that can never be perfected; but, it can be improved upon over time. This involves not only critical thinking skills, but also heuristic methods that allow one to make decisions with imperfect solutions, incomplete information, and a finite amount of time; over time, one gains more information, hopefully more options, and a more efficient decision-making process.This is a topic for another day, as it is a separate thing altogether from understanding logical fallacies. Nevertheless, understanding logical fallacies may help to fine-tune one’s critical thinking, intuition, and decision-making processes, and help to filter out unhelpful, incorrect, or even dangerous information that one is sure to come across if active in online patient communities.

References

Its amazing to me that someone like you who is extremely arrogant and puts off a know it all vibe would write a post about logical fallacies. A post that has fallacies of its own and you yourself with no background (Bachelor, or graduate degree) in anything trying to tell us patients we shouldn’t listen to everyone on the internet but obviously should listen to you. Idiot. Show me the evidence. Yeah. Hypocrite.

I’m not convinced you’ve even read the article, as you are claiming I said things that I didn’t say. The ad hominem attacks and the appeal to accomplishment fallacy in your comment make me think that, while you didn’t put a lot of thought into your response, you are certainly emotionally invested. So, although you lack the resolve to post under your actual identity, maybe you can at least take the time to explain what fallacies I’ve committed?